Is the Bible Inerrant? No—And That’s a Good Thing

Why Letting Go of Biblical Perfection Can Set You Free

I. The Burden of Biblical Perfection

Somewhere along the line, someone told you the Bible was perfect or “inerrant.”

Maybe it was a Sunday School teacher who said, “The Bible is the literal Word of God, every word is true.” Or maybe it was a preacher who thundered that Scripture is without error, cover to cover, and if you don’t believe that, your faith is on thin ice.

But then you read it. And you noticed a few things. Like, there are two creation stories—and they don’t match. Or you read Kings and then Chronicles and wondered, “Wait, didn’t that king die a different way in the other book?” And you found Jesus saying, “You have heard it said… but I say to you,” and thought, *”Hold on—isn’t he contradicting Scripture?“

You’re not alone. The truth is, the Bible is not inerrant. It never has been. And that’s not only okay—it’s good news.

Because the Bible doesn’t need to be flawless to be holy. Just as it doesn’t need to be a divine dictation to be sacred.

It was never meant to be a weapon or a rulebook. Rather, it is meant to reveal, testify, or proclaim the unfolding, often messy, always love-drenched story between God and humanity.

II. Before It Was Written, It Was Told

Long before ink hit parchment, Scripture’s stories were spoken aloud. Around campfires. At temple festivals. In exile. At home.

The earliest biblical texts emerged from this “oral tradition”—narratives shaped and reshaped by generations who told the stories that mattered to them. The story of creation? Passed down from one generation to the next for centuries before anyone wrote the first phrase of Scripture, “In the beginning.”

And guess what? The creation and flood stories found in Genesis aren’t even unique to the Bible. They echo myths from other ancient cultures, like the Babylonian Enuma Elish and the Epic of Gilgamesh. That’s not plagiarism; that’s what these ancient cultures did—they adapted, interpreted, and theologized the stories they inherited to make sense of their world and their God.

So from the very beginning, the Bible wasn’t written to be a factual record. It was written to convey truth through story, myth, metaphor, poetry, and praise.

III. The Bible Contradicts Itself (Spoiler: That’s Not a Problem)

Let’s just say it out loud: the Bible doesn’t agree with itself.

There are two creation stories in Genesis:

- Genesis 1: a cosmic, ordered creation over seven days.

- Genesis 2: a dusty, earthy creation with a man formed from the ground before plants even show up.

There are two histories of Israel:

- 1 & 2 Kings paint a pretty raw, sometimes harsh picture of the monarchy.

- 1 & 2 Chronicles clean things up with a little spin, focusing on temple worship and presenting King David and King Solomon in a brighter light.

Why? Because different authors had different agendas. Kings likely came from the “Deuteronomist tradition” during or after exile—trying to explain Israel’s fall as divine punishment. Chronicles came later, reflecting “priestly” concerns and post-exilic hope.

Even the prophets disagree. Some predict things that never come true. Others reinterpret failed prophecies in light of new revelations.

So, if your view of the Bible requires perfect consistency, you’re in trouble. You won’t find it there. But if you’re okay with a living, breathing collection of human-divine interaction, you’re in for something beautiful.

IV. Jesus Didn’t Read Scripture Literally—So Why Should We?

Let’s be clear: Jesus was a devout Jew, and he knew his Scripture inside and out. But he didn’t treat it like a legal contract.

Instead, Jesus told stories: “The kingdom of God is like…” And he challenged old interpretations: “You have heard it said… but I say to you.”

He broke Scriptural rules when compassion demanded it. And he refused to condemn others who did (like when he refused to condemn the woman caught in adultery, even though the Law was clear).

Clearly, Jesus interpreted Scripture through the lens of love, liberation, and divine intent—not rigid literalism. He treated the text as sacred, but never as shackles.

So if the Son of God wasn’t a biblical literalist, why would strive to be?

V. The Gospels Disagree—And That’s Okay

Take the resurrection story–the central story of the Christian faith. And yet, if you ask the four gospel writers what happened, you get four different answers:

- Mark: The women flee from the empty tomb and say nothing to anyone (the earliest manuscripts end here).

- Matthew: There’s an earthquake, an angel, and a reunion in Galilee.

- Luke: Jesus appears to two travelers on the road to Emmaus.

- John: Mary mistakes Jesus for a gardener before recognizing him.

Which version is the “right” one? Which is the “factual” one?

But maybe these are the wrong questions to ask. Maybe these stories aren’t about factual details as much as they’re about truth… about grief turned to hope… about fear giving way to faith… about the risen Christ meeting people in the middle of their confusion and doubt and leading them into new life.

VI. Paul vs. James (Because Even the Early Church Argued)

Paul says: “We are saved by grace through faith, not by works.” (Ephesians 2:8-9) James says: “Faith without works is dead.” (James 2:26)

Which is it? Both? Neither?

The early Church didn’t have one monolithic theology. It was a community of people wrestling together with how to follow Jesus in a complicated world. That tension is preserved in Scripture—on purpose. It shows us that questioning, disagreeing, and evolving are not threats to faith. They are the practice of faith.

VII. Historical Criticism, Literary Criticism, and the Beauty of Complexity

Thanks to generations of biblical scholars, we now understand:

- The Bible was written by dozens of authors, in different languages, over 1,000+ years.

- Many books had multiple editors, sources, and redactions (like the J, E, D, and P sources in the Torah).

- Literary forms matter: you don’t read Psalms like you read Romans. Or Revelation like you read Genesis.

Historical and literary criticism doesn’t destroy faith. It refines it. It gives us eyes to see the Bible for what it is: not a static rulebook, but a dynamic, multi-voiced conversation between God and God’s people.

VIII. The Bible Is a Library, Not a Rulebook

Imagine walking into a vast, ancient library.

Some books are poetry. Others are letters. Some are fiery sermons. Others are prayers. Some are dreams and visions that border on the psychedelic. While some books contradict others. And all of them are trying to make sense of one thing: Who is God? And who are we in light of God?

That’s the Bible.

It’s not a divine monologue. It’s a sacred conversation. And like any good library, it doesn’t hand you a single, simple answer. It invites you into the mystery.

IX. The Arc of Scripture Bends Toward Love

When you step back and look at the whole sweep of Scripture, a pattern emerges:

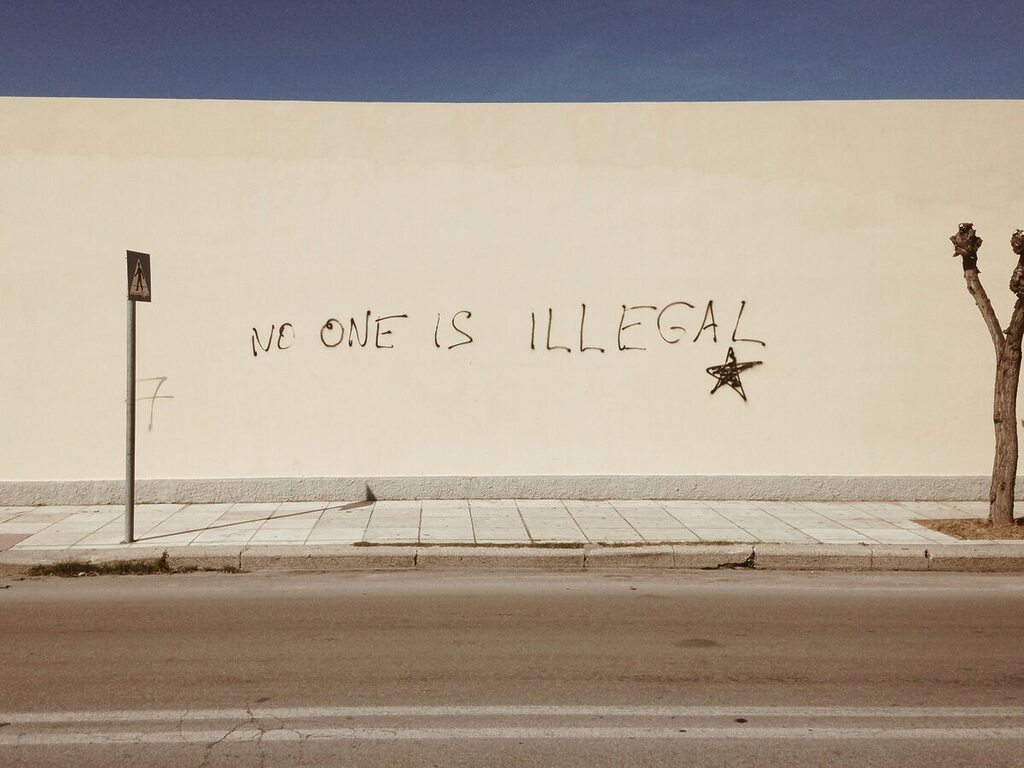

- From exclusion to inclusion.

- From vengeance to mercy.

- From law to love.

- From purity codes to radical welcome.

Yes, there are troubling texts—texts of violence, exclusion, and patriarchy. But they don’t get the last word.

Because the story of Scripture is not about a God obsessed with control. It’s the story of a God in relentless pursuit of love. A God who partners with us. And who walks with us. And who frees us—again and again—from the worst things we do to each other.

X. So What Do We Do With the Bible?

Read it. Wrestle with it. Question it. Engage it with curiosity. Let it inspire you; disturb you; and transform you.

But please don’t worship it.

The Bible is not God. It points us toward God. It helps us see God’s heart. And when we stop demanding that it be perfect, we just might discover how perfectly it reveals a love story that never ends.

Subscribe to The Inclusive Christian and join a growing community of people reclaiming faith, Scripture, and Jesus from the grip of fear and fundamentalism.

Because you don’t have to check your brain at the Church door to follow Jesus. And you don’t need a perfect Bible to experience perfect love.